התחל במצב לא מקוון עם האפליקציה Player FM !

Chasing Butterflies: Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida – Part 2, José Prieto’s story – Podcast 146

Manage episode 447094644 series 2414495

Previously on Chasing Butterflies – Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida:

Manuel Conde had lived several lives even before he moved to Miami, Florida. He’d been born José Conde Samaniego in 1917 in Galicia, in northern Spain, though his family fled to Cuba after General Franco’s fascist coup d’état in the 1930s. And then, in 1959, Castro overthrew the government and enforced Communist rule over Cuba. Manuel, having already fled one dictatorship in Spain a few years earlier, took his family and fled to Miami, Florida, smuggling out a sexploitation film that he’d just made, called Girls on the Rocks.

In Miami, Manuel met Dolores Carlos. Dolores was a newly semi-famous actress and model on the local scene, having starred in (and been arrested for) a successful nudism film, Hideout in the Sun (1960) made by Doris Wishman, which she followed by appearing in a handful of other nudie cutie films.

Dolores introduced Manuel to the growing community of ex-pat Cuban filmmakers that had settled in south Florida after Castro’s coup, and together they shot a nudie short in 1961, Playgirl Models.

Dolores and Manuel arranged a meeting with Leroy Griffith, an energetic, entrepreneurial force of nature, who’d recently moved to Miami and made a name for himself by acquiring a string of theaters where he exhibited burlesque shows and then adult sex films. The three of them made a full-length feature was called Lullaby of Bareland (1964).

In 1966, Manuel and Dolores teamed up with Leroy Griffith to make a film with a decent budget – Mundo Depravados – starring Tempest Storm, one of the country’s best-known burlesque performers, and the movie was ostensibly directed by her husband Herb Jeffries, a suave and seductive film and television actor and popular jazz singer who had a large following in the African American market. ‘Mundo Depravados’ was released with eye-catching promo material – “A Sinerama of Sex and Fear!” – and is one of the most bizarrely entertaining film experiences you can have.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many of these people. Their overlapping personal histories reveal an untold chapter of adult film history and the hidden role that Cubans played in shaping it.

These are some of their stories. This is Chasing Butterflies, Part 2: José Prieto’s story.

You can listen to the Prologue: Dolores Carlos’ story here, and Part 1: Manuel Conde’s story here.

With thanks to John Minson, Tom Flynn, Ronald Ziegler, Leroy Griffith, Veronica Acosta, Marcy Bichette, Mikey Bichette, Lousie ‘Bunny’ Downe, Mitch Poulos, Sheldon Schermer, Ray Aranha, Manny Samaniego, Barry Bennett, Randy Grinter, Herb Jeffries, Tempest Storm, Chester Phebus, Michael Bowen, Norman Senfeld, Richard Falcone, Lynne O’Neill, Something Weird Video, and many anonymous families and friends who have offered recollections, large and small, over the years.

This podcast is 40 minutes long.

*

1. José Prieto – Timing

They say timing is everything. Sometimes it’s a well-oiled, precision-calibrated clock, but other times it just kicks you in the balls.

Take José Prieto, for example. It was the late 1950s, and here was a man who’d spent his entire life waiting for that big break that would give his life meaning, that would fulfill his dreams, but fate always seemed to be a case of wrong place, wrong time, and that elusive, life-changing moment of success remained forever out of reach somewhere off on the horizon. José was a small, wiry man, consumed by nervousness, and his world-weariness hung on him a cheap, oversized suit. His head seemed constantly lowered as if trying to figure out the answer to life’s latest conundrum. Some dismissed him as dour and uncommunicative, but José had close friends who knew the truth. Guys like Greg Sandor or Rafael Remy. They’d worked with him in the Cuban movie business over the years, stuck around to get to know the real José, and found him a quiet, thoughtful, smart, and diligent man. Funny and mischievous even, especially when he’d had a few El Presidentes in him.

José Prieto was Cuban-born and Cuban-raised. He’d lived in the country’s capital, Havana, all his life: it was a city of well over one million inhabitants, but it felt like a village to him. He mixed unobtrusively with everyone, from high-level government officials to pimps, petty criminals, and low-level gangsters. It wasn’t that he was particularly affable, but more because he wasn’t considered a threat to anyone. He knew his country wasn’t perfect: it was overseen by Fulgencio Batista, an un-elected right-wing military dictator who’d taken power by force in 1952. Batista’s regime was corrupt and becoming increasingly repressive, but José was smart enough to know the secret to living a comfortable life in Cuba was to fly below the radar and avoid the attentions of the men in power. If you kept your nose clean and your wits sharp, you could navigate this world comfortably.

And so, José had become a proficient jack of all trades in the Cuban TV and film business. The 1950s was a ‘Golden Age’ for Cuban cinema: it started when many American films were screened in theaters across the country, partly due to Batista’s close ties with the U.S. government and business interests – and then continued when several American films were shot in Cuba during this time, taking advantage of the island’s proximity and exotic appeal. Suddenly local studios were established in Havana which increased local TV production. Cuba became one of the first Latin American countries to introduce television in the 1950s, which quickly became popular, producing a variety of hit shows, including comedies, soap operas, and live music programs.

In a career that had been going over 20 years, José had produced, lit, shot, even acted in tens of these productions. Most of all though, he saw himself as a director, and occasionally he got the chance to be in charge. Some of his productions had been hits, others came and went virtually unnoticed, but he ploughed on, waiting for that one opportunity that would establish himself as a major player. But the Cuban film industry, for all of its strengths, was still small compared to Hollywood or Mexico, and the big breaks never came his way.

*

2. ‘Our Man in Havana’ (1959)

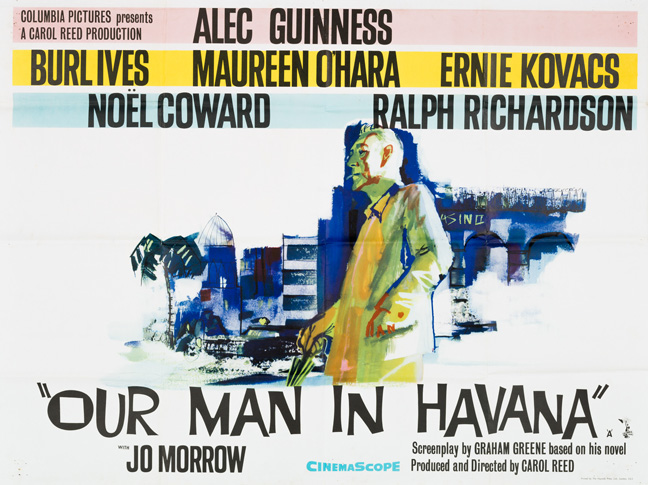

And then, José’s timing changed, and he was suddenly in the right place at the right time. It started when he read that Columbia Pictures were going to shoot a major motion picture right there in Havana. Not only that, but it involved three of his favorite people: it was to be directed by Sir Carol Reed, it would star Sir Alec Guinness, and it was based on a new book by Graham Greene named Our Man in Havana.

The story was a satire that mocked the intelligence services, especially the British MI6, and their willingness to believe reports from their local informants. Alfred Hitchcock had been the early favorite to make the film, but he backed out when he couldn’t afford the film rights to the novel.

José had read and admired the novels of Graham Greene, especially ‘The Power and the Glory’ and ‘The Heart of the Matter’, and his interest in the upcoming movie production only increased when it was announced that the film’s cast would include English acting royalty, Ralph Richardson and Noël Coward, as well as American stars like Burl Ives, Maureen O’Hara, and Ernie Kovacs, to help sell the film to an American audience.

José’s opportunity came in the last weeks of 1958, when Graham Greene and Carol Reed visited Cuba. They were there to do two things – view locations and hire the local crew. When they arrived, Reed was shocked and concerned by what he saw on the streets of Havana: signs that Batista’s regime had become more vicious were everywhere, and Reed was concerned about how filming could take place against the backdrop of such violence and intimidation, after all, Greene’s book was hardly reverential to the Cuban dictator. Columbia Pictures suggested a local production manager as a solution: a real life ‘man in Havana’ who could navigate the political and logistical roadblocks.

José saw his big chance and wrote to the studio asking to be considered. He was granted an interview, and made an impassioned case: he was more than just a fixer, he said. Havana was his backyard. He knew almost everyone, and if he didn’t know someone personally, well… he knew someone who did. He was experienced in putting together a movie production, he could arrange a complex shooting schedule, and he could do everything else that you couldn’t put a price on.

Where would they find film equipment? José assured them that whatever they needed would be delivered immediately.

Where would the best production accommodation be? José would get the choice rooms in the top hotel in Havana – the famous pink and white Capri Hotel, in reality, a casino cum whorehouse, owned by the Florida mobster Santo Trafficante, Jr., which was fronted by the entertainer, George Raft.

How would they find actors, or extras for the street scenes? José would produce any number of eager locals, excited to be in a big film production.

What about the nightclub scenes… where could those be filmed? No problem, said José. He had a cousin who worked at the Tropicana, Havana’s most notorious nightclub, another location owned by the mob. What’s more, he could arrange for strippers, bartenders, and local business men to be extras in the scene as well.

The production team was impressed. José had the experience, technical knowledge, and the network of contacts that they needed. He was hired on the spot, and in the records of the production, he was given the credit of ‘Assistant Director (Cuba location scenes)’. He even found jobs on the shoot for friends like Greg Sandor and Rafael Remy. Both had good credentials, having worked in local and international productions, Remy having already been an uncredited assistant director on John Sturges ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ (1958) starring Spencer Tracy, which had shot in Havana in the summer of 1956.

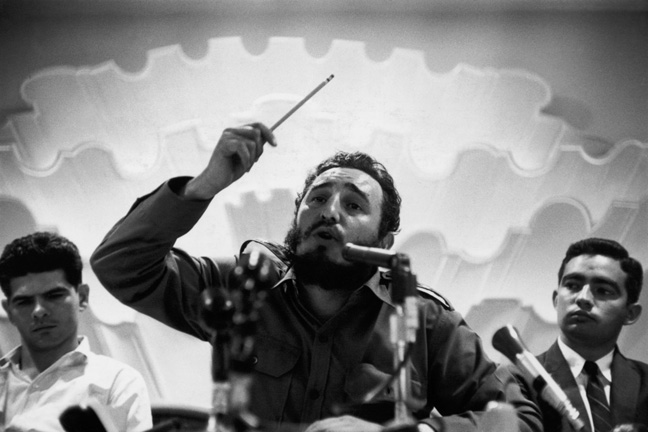

And then on January 2nd 1959, the revolution happened: Fidel Castro overthrew Batista’s regime and the situation in Cuba changed overnight: military thugs carrying sub-machine guns were everywhere and wagons laden with peasants in chicken-wire cages were drawn through the streets.

It was a strange time to be starting filming a satire about spying, but the news wasn’t all bad for the film production: Graham Greene had been friends with Castro since an earlier visit, and he wasn’t fazed by any new problems the coup would cause. After all, their film mocked the previous regime of Batista in an unflattering light and also condemned American and British meddling: surely Castro would welcome this prestigious film production – and appreciate the celebrities from England and the United States. The first signs were good: the new revolutionary government of Cuba gave the green light for ‘Our Man in Havana’ to be filmed in the Cuban capital, and so the production moved forwards.

But the same treatment was not applied to José. He was now treated with suspicion by the new leaders: Batista’s government had always let him do what he wanted but, bizarrely, he was now considered part of the former regime by Castro’s new government departments – and that made his new job rather more difficult.

His first task, before the film started, was to apply for work permits for everyone. This entailed taking the script to the new Ministry of Labor and justifying each cast and crew position to them. Castro’s men listened and then complained that the novel didn’t accurately portray the true brutality of the Batista regime.

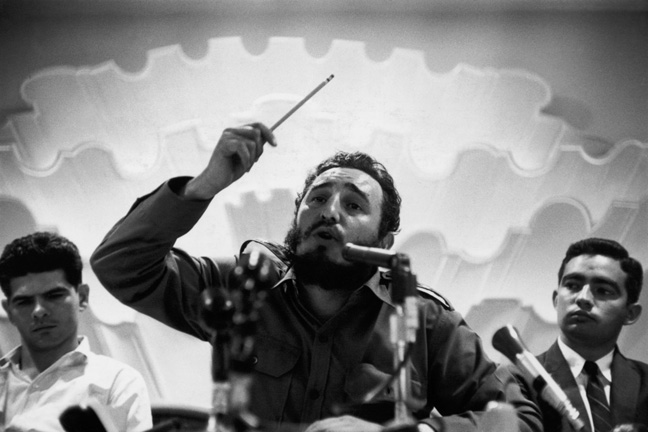

Early Castro press conference, 1959

Early Castro press conference, 1959

Then José received an unexpected offer. The casting director told him they needed a local to play the part of Lopez, Alec Guinness’ assistant in the movie. When José found them a selection of actors, the production team was unsatisfied. The casting director replied that the ideal person for the acting role was José himself. It was a significant part, with plenty of lines and screen time.

José wasn’t keen. He was a background kind of guy, he said. Sure he’d acted before, but he was someone who preferred to stay in the shadows. His concerns were dismissed, and Alec Guinness was rolled out to try and convince him. Guinness took him aside and told him that both of their characters were anonymous personalities, mere cogs in the bigger story, men being manipulated by the machinery of government and men in power. Guinness said that it was important that neither of them acted: they just had to “be”. In that way, José’s personality was perfect for the role. In fact, his protestations were proof that he was the right choice. José was cornered: he’d idolized Guinness since the days of ‘The Third Man’ so how could he pass up the occasion to act with the great man? He reluctantly took the role – which he did in addition to keeping the job of local assistant director.

(l-r) Alec Guinness, José Prieto

(l-r) Alec Guinness, José Prieto

Filming started on location in Havana in March 1959 just two months after the overthrow of the Batista regime. On the second day of filming, José was approached by an official from the Minister of the Interior demanding a copy of the screenplay. José explained he’d already provided this to Ministry of Labor. That was irrelevant, he was told. Furthermore, they wanted a full translation – and, a censor would be sent to the set each day, in addition to a government observer, both of whom would shadow José and check that he was not doing anything that was “compromising the revolution.” It made José’s life more painful, especially considering that the Ministry of the Interior quickly insisted that 39 changes be made to make it appear that life during the Batista regime had been even more unfavorable.

At other times, José’s work on the movie was more comical but no less serious. Take beards for example: since Castro took over, a beard had come to represent a hero of the revolution. But one of the characters in the film – who played the role of Batista’s chief of police – had a beard. José was called in by the Castro officials and told that all beards in the cast and crew had to disappear.

Unwanted pressure didn’t just come from the new government, it came from locals too: when extras dressed up in the blue uniforms of the Batista police turned up for filming, they were attacked by angry spectators. Once again, José had to intervene to find a solution.

(l-r) José Prieto, Alec Guinness

(l-r) José Prieto, Alec Guinness

And then José got a message from Castro himself: the leader wanted to meet the people responsible for the production: Carol Reed, Graham Greene, Noel Coward and Alec Guinness. They were invited to Castro’s bungalow for the day. This would mean losing a whole day of shooting, so José went back and, in a diplomatic fashion, told Castro’s office that it would be difficult to accommodate. It was the wrong answer: José had greatly displeased the leader. He was dispatched back to the film set with a new instruction: the request had now become a demand, and the team were told to meet with Castro the following day.

So the next day, Reed, Greene, and Coward turned up for the appointment with an uncomfortable José lurking in the background. They waited for Castro in a palace room surrounded by bearded revolutionaries who informed them that Castro would be turning up shortly. Minutes turned into hours, and José’s unease turned into terrified concern. In the end, the film team left without a meeting. Castro had made his point. Days later, on 13 May 1959, Castro did meet the film crew when he visited the set while they shot scenes at Havana’s Cathedral Square. After he posed for pictures, Castro spoke to the press saying, “Any film company can make any picture they want in Cuba. There will be no censorship in my country. You can make the film exactly as you please. Those are my orders.”

(l-r) Maureen O’Hara, Fidel Castro, Alec Guinness on the set of ‘Our Man in Havana’

(l-r) Maureen O’Hara, Fidel Castro, Alec Guinness on the set of ‘Our Man in Havana’

Not strictly true, however. The on-set censor continued to make frequent demands to José that changes be made – in one of the nightclub scenes, for example, he felt that too much leg and breast was visible. Another time, he demanded that the whole day’s shooting footage be handed over to him for cuts to be made. But José had grown in confidence, and now he refused, standing up increasingly to the authorities, and invariably winning more battles along the way.

José did his job well in a way that few others in the world would’ve been able to do, and the film company was pleased with him. He’d done the hard, silent, behind-the-scenes tasks, delivering anything that was requested without fuss, in his usual intense, quiet, and serious manner. He earned the nickname ‘José Practical’ as a result of the calm, pragmatic way he worked.

(l-r) José Prieto, Jo Morrow, Alec Guinness

(l-r) José Prieto, Jo Morrow, Alec Guinness

But privately, José was far from feeling calm, and his fears were growing stronger by the day. He knew he’d be protected from Castro and his generals for the duration of the filming, but what would happen after the crew packed up and went home? He’d stood up to the government heavies on countless occasions during the film shoot, but how would they treat him in the future?

At the end of seven-week shoot, José started noticing things. Friends told him they’d been approached and quizzed about him. They’d also been asked questions about his local associates on the movie, like Greg Sandor and Rafael Remy. He noticed his mail was going missing, and he wasn’t paranoid by nature, but was he imagining it or was he being followed every day when he set out to go to work?

It was too much for the veteran film man. He called his contact at Columbia Pictures and asked to have his name removed from the credits of the final version of ‘Our Man in Havana.’ He got a mixed message. They told him they could drop the ‘Assistant Director’ credit, but that the acting credit was unavoidable. After all, his face was up there on the screen for all to see. José tried putting his foot down, but he was told that the best they could do was for him to use another name. José was relieved, but, somewhere along the way, the instruction was lost, and when the film came out, the name ‘José Prieto’ was prominently displayed in the credits – just after the big-name English and American actors.

José didn’t want to hang around. In the aftermath of the film, he wanted out before he got picked up and found himself in trouble. He packed his bags, and fled the country, heading over the sea to a new life in Miami.

*

3. Life in Miami

José didn’t move to Florida by himself. He was accompanied by his two main compadres in the Havana film business, Rafael Remy and Gregory Sandor. The grass looked greener on the other side of the water for all three, and so in 1961 they embarked on new lives in America. The U.S. was the center for capitalism and the center for filmmaking, right, so why not become part of the gravy train? They figured they could seek work quietly at first and earn a steady living in Florida. In fact, it was Sandor that facilitated their move as he was an American, hailing from Burbank, California.

Each of the three men wanted to continue working in the film business, but each had a different plan. The one thing they all had in common was that they wanted low profiles, to work under the radar, at least at first, with José especially fearing possible reprisals from the Cuban government.

Greg Sandor had it easiest: being an American who’d lived and worked in Cuba for years, he was the least worried. He was essentially a cameraman, who saw that his best opportunity would be in the world of commercials and industrial films.

For José and Rafael, it was more difficult. As new immigrants in the country, they headed to the Freedom Tower in Miami – the central location used by the government to process and document refugees from the Cuban Revolution that administered the Cuban Refugee Program.

Rafael Jesus Remy was always the more cavalier one. His plan for anonymity was to find film work, any film work he could, but use a variety of mildly different names to mask his participation. Sure enough, over the next years, he would be known as Jesus Remy, Gerry Remy, Ralph Remy, and many others – sometimes even his actual name Rafael Remy.

As for José, he was the fearful one. Film work was all he knew, but he’d had direct – and often confrontational – contact with Castro and his men, and so was reluctant to do anything that might draw attention to himself. He was the first of the three to find work – a lowly bellboy position in The Everglades Hotel, a popular mid-range option for business travelers in downtown Miami. It was a steep and strange decline in status for a man who was coming off being an actor and assistant director on one of the biggest motion pictures of the decade.

Everglades Hotel, Miami – late 1950s

Everglades Hotel, Miami – late 1950s

One night the three amigos found themselves outside a tiny shopfront in Little Havana in Miami with a sign outside advertising a fortune teller. They’d had a few drinks and laughed their way into the cramped room, where each sat on an upturned fruit basket and in turn had their future explained to them by a mysterious woman adorned in scarfs and jewelry. The mystic explained she used a combination of sacred instruments, including palm nuts, pieces of coconut, and Spanish tarot cards, to see into the future. She told them solemnly that Greg Sandor would find money and respect. José would find fame and notoriety. Then she paused, as if alarmed by the reading: Rafael Remy would find trouble and strife.

Inevitably perhaps, all three of the filmmakers came into contact with Dolores Xiques, now more commonly known by her film and modeling name, Dolores Carlos. She introduced them to the Cuban expat community, a group growing larger by the day but one that was still tight-knit. At the heart of it was Dolores, the caring mother hen looking after men from a country that she’d never visited but that she felt passionately about. She’d become the connective tissue binding the community together.

Dolores became particularly close with José. It was an unlikely friendship: she was an American single mother in her early 30s, living with her teenage daughter Marcy, and was the star of scores of nudie films and men’s magazines, who had the trust of film producers, theater owners, movie directors. and crew members. He was a dour, taciturn Cuban filmmaker in his late 40s, often paranoid and fearful, struggling with having left his country so hurriedly.

Dolores took José to see her friend K. Gordon Murray, the film producer whose company Trans-International Films bought children’s movies from Mexico and dubbed them for the domestic market. She was still trying to persuade Murray to finance nudie pictures, but apart from re-releasing a perfunctory effort called Eve or the Apple (1962), featuring nudie inserts of Dolores, she hadn’t had much luck in convincing him. He was making too much money with colorful, surreal fairytale films, like ‘Santa Claus’ (1959). But Dolores was persistent, convinced that Murray would eventually come good and move into film production, and she took many Cubans she met at the Freedom Tower to his offices at 530 Biscayne Blvd in Miami. Murray was impressed with José, especially when he recognized him from his appearance in ‘Our Man in Havana’. He found work for José on a variety of film projects, which José accepted if he could them fit in around his Everglades Hotel doorman duties.

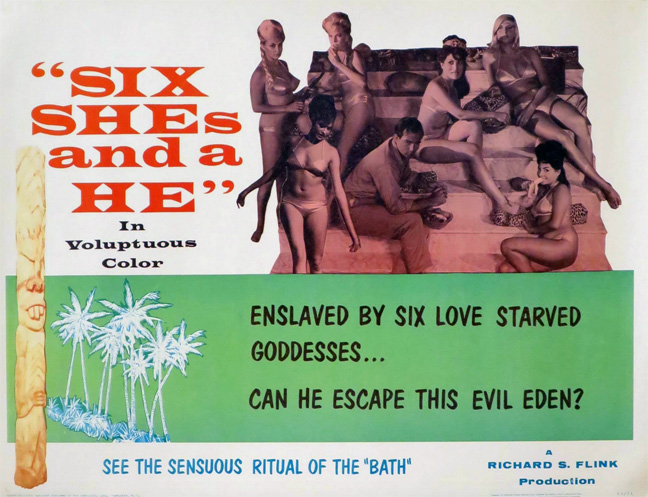

Dolores also connected José with other filmmakers, many engaged in making South Florida nudie pictures. José became popular, willing to do a variety of jobs, invariably uncredited, often underpaid, but always skilled, professional, and useful. Just one job credited his involvement: an assistant director job for the Cuban man-of-many-hats, Frank Malagon. Malagon had set up a film studio to make films as a way of funding his anti-Castro activities, and his first feature was a nudist movie, Six She’s and a He (1963). Malagon’s partner, Richard Flink, was credited with directing the film but as neither Malagon nor Flink had much experience, it was largely directed by José himself. Many of the crew roles on the film, as with many other similar efforts at the time in Florida, were taken by expat Cubans – which made José feel at home.

In the early 1960s, in his first years in America, José worked on tens of films in an uncredited capacity. The Everglades Hotel provided him a one-room lodging in the basement of the building and he worked shifts there, so if was given enough notice, he could usually arrange to be free to work on a film set.

*

4. ‘Dios te salve, psiquiatra’ (1966)

In 1966, José received a call from his old friend, Greg Sandor. Sandor had done well since they’d arrived from Cuba. He’d found cinematography work on commercials in California, as well as camera work on a few exploitation films. His recent credits included a couple of Ted V. Mikels films, ‘Dr. Sex’ (1964) and ‘One Shocking Moment’ (1965), as well as two Roger Corman produced, Monte Hellman-directed films that starred Jack Nicholson ‘The Shooting’ (1966) and ‘Ride in the Whirlwind’ (1966).

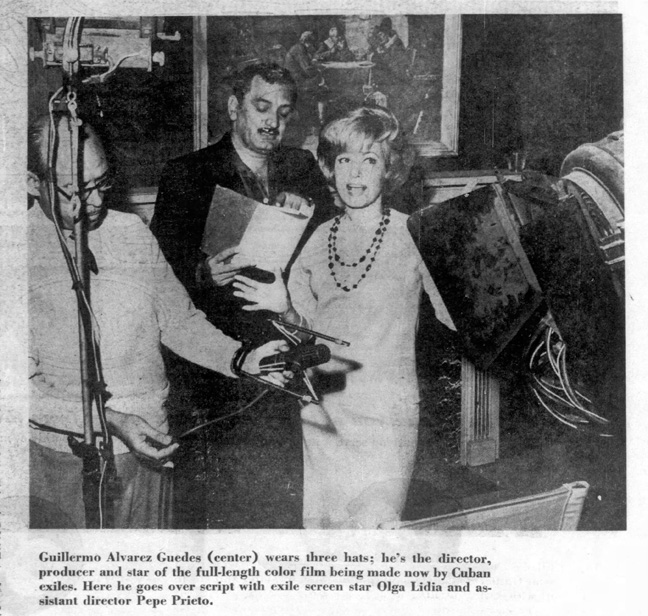

Despite his growing success, Sandor had kept ties with his Cuban countrymen in Florida, and he had an idea for José. Sandor was helping another Cuban immigrant, Guillermo Álvarez Guedes, put together a Spanish language production, Dios te salve, psiquiatra (‘God Bless You, Psychiatrist’). Sandor said to José that the time had come for them all to come back and work together again just like in the old days in Cuba. Times were changing, he said, and José should be less fearful and more ambitious, and seek better quality film jobs. Sandor also enlisted Rafael Remy for the new film, as well as other members of the Cuban community in Miami.

José took some persuading: being a bellboy for the past years had been demoralizing at first, but it had given him an easy and quiet existence. Giving that up was a risk. José sought advice from Dolores and K. Gordon Murray and both encouraged him to strike out for himself, and return to more regular film work. Murray even promised him film projects that would be funded by his company. So José accepted the job of assistant director, on condition that his on-screen credit would only refer to him as ‘Pepe Prieto.’ He took a temporary leave of absence from the Everglades Hotel for a few months to be the assistant director on the film. The management at the Everglades liked José and were understanding, but also a little skeptical: they told him they’d keep his position open for a while – just in case this film malarkey didn’t work out.

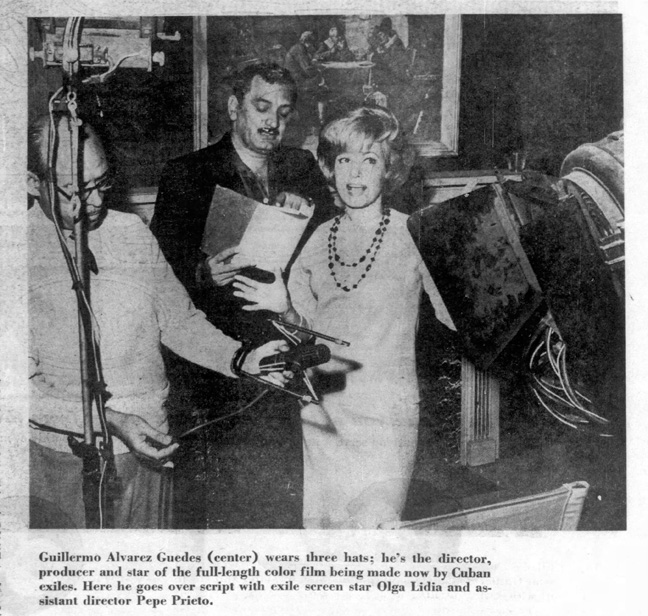

(l-r) José Prieto, Guillermo Alvarez Guedes, Gina Romand

(l-r) José Prieto, Guillermo Alvarez Guedes, Gina Romand

‘Dios te salve, psiquiatra’ was a broad comedy of roaming love and Latin muchachos, and starred Gina Romand, a Cuban-born, big name in Mexican films of the time. It was a solid and bankable project, but most of all, it was a reunion of old friends: everyone returned to work for lower salaries simply because they wanted to re-connect with each other again. Talent that had been dormant for years suddenly returned to life. Dolores put together the promotional push that resulted in extensive media coverage and a big premiere. The film turned out to be a modest success in Spanish-speaking areas of the country.

José’s first job after ‘Dios te salve, psiquiatra’ was a quickie, Sting of Death (1966), about a deformed man working for a marine biologist who takes revenge on the people that mock him by experimenting with a deadly jellyfish. The film was another for the studio established by Frank Malagon, for whom he’d directed the nudist movie, Six She’s and a He (1963) a few years earlier, and José still just wanted his on-screen credit to just refer to him as ‘Pepe Prieto.’

And then Dolores called. Her long-term strategy with K. Gordon Murray was finally starting to pay off: after years of trying to persuade him, she’d convinced him to fund an exploitation film. Murray insisted that the craze for nudie movies had long passed: instead, he was looking at a more topical feature, albeit something that would still appeal to the sex-and-violence drive-in audiences, and he told Dolores that he’d found the right vehicle and wanted her help. Murray was looking to make a film that would hit the jackpot – and he wanted to know if José would be interested in directing?

*

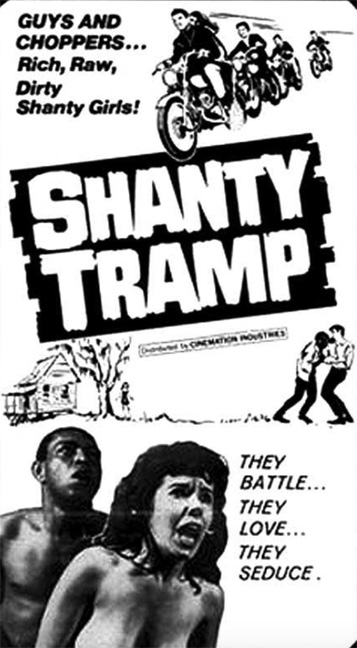

5. ‘Shanty Tramp’ (1967)

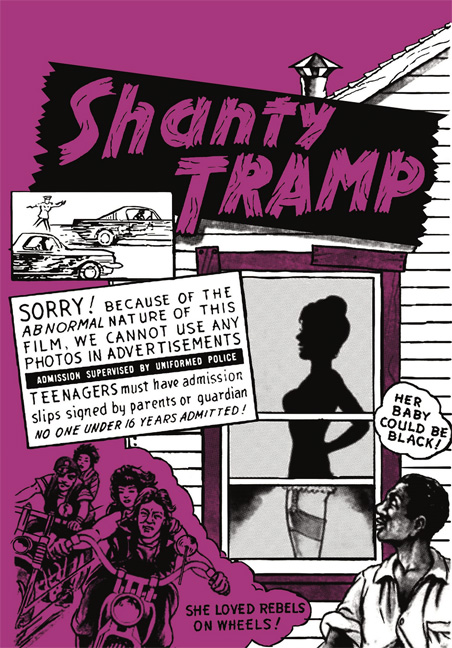

Shanty Tramp (1967) is one of the most notorious, shocking and scandalous films of the 1960s. It tells the story of a sleazy evangelist who makes a play for a small town’s local tramp, but he’s shocked when he finds that she prefers a local black man over him. Furious, he stirs up the town against the couple causing fights, murders, lynch mobs, ruined reputations, and broken homes.

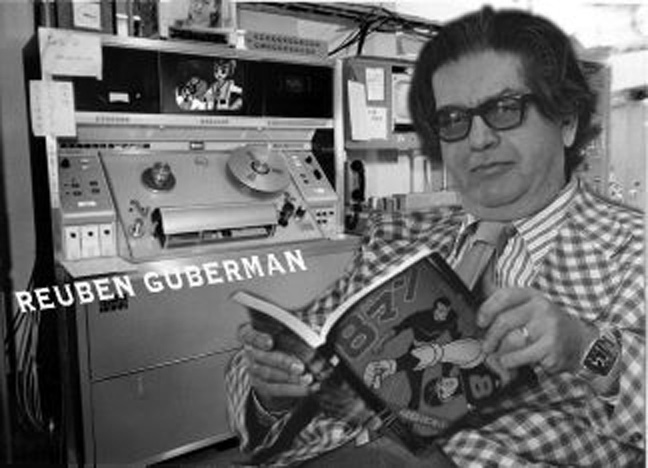

So who came up with the whole concept? The incendiary script, with plenty of nudity, sex scenes, and violence thrown in, was largely written by one of K. Gordon Murray’s staff members, Reuben Guberman. Guberman was a flamboyant New Yorker – or a “fat, Jewish maverick” by his own description. He’d left New York many years before as a teenager to seek his fortune in sunny Miami, Florida, and embarked on a ridiculously varied career that included being a hamburger cook, a drive-in restaurant manager, radio announcer and producer, editor of the weekly Dade County Times-Union newspaper, and political candidate. Perhaps his most surprising career move was discovering that he had a natural gift for lip-synchronization – an essential component part for dubbing foreign films and cartoons for Murray.

When Guberman met K. Gordon Murray it was a match made in heaven. Together they invented the looping process of dubbing: this consisted of splicing short segments of dialogue from a movie into a loop, and then playing them back to the voice actor allowing them to watch the film-loop over and over and record an English language track matching the on-screen actors’ mouths as much as possible. Working for Murray in his tiny office in nearby Coral Gables which he called Soundlab Inc., Guberman’s job was to translate the original language scripts into English dialog for the voice-talent, and in many cases, he also provided some of the voices himself as well.

But by the end of mid 1960s, the market for dubbed films was waning, and both Murray and Guberman were looking for a new market: they decided that ‘Shanty Tramp’ should be their next project. Murray and Guberman had already started to put the film together and hire a number of the actors when they offered the directing gig to José. José accepted even though he was still working at the hotel: he was hungry and ready to return to the party. Being the head-strong, stubborn guy he was, his first step was to fire most of the actors who’d been offered parts, and he assembled a crew almost completely composed of Cuban expats from his Little Havana hangouts. At the heart of the new film project was his old friend Rafael Remy who ended up doing both the cinematography and editing.

‘Shanty Tramp’ credits showing the Cuban crew

‘Shanty Tramp’ credits showing the Cuban crew

If the subject matter was akin to lighting a touchpaper of controversy, the casting of the movie proved to be a forest fire. José wanted proper actors for the lead roles, not the usual untrained and inexperienced sexploitation regulars, so he turned to Dolores and asked her to find suitable principals for the film. Dolores knew all the Cuban crew workers in Miami, but her knowledge of actors – especially serious thespians – was less thorough. She had an idea though: her teenage daughter, Marcy, had recently started acting semi-professionally with the Miami Merry-Go-Round Playhouse, and Dolores – ever supportive of Marcy’s endeavors – was a regular in the audience. She’d become friends with some of actors there, and successfully approached a number of them for the main roles in ‘Shanty Tramp.’

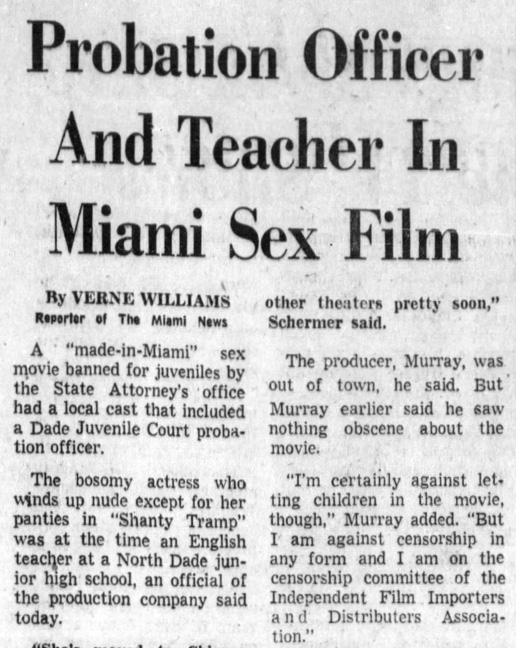

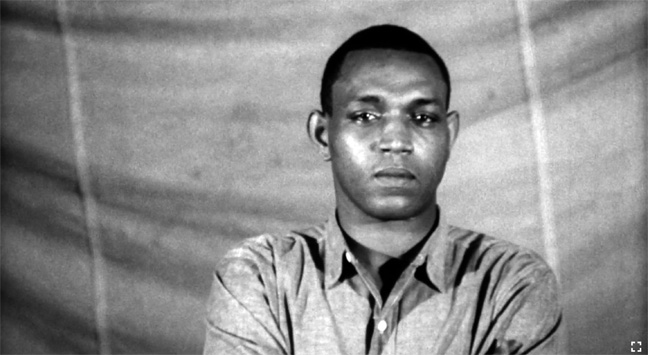

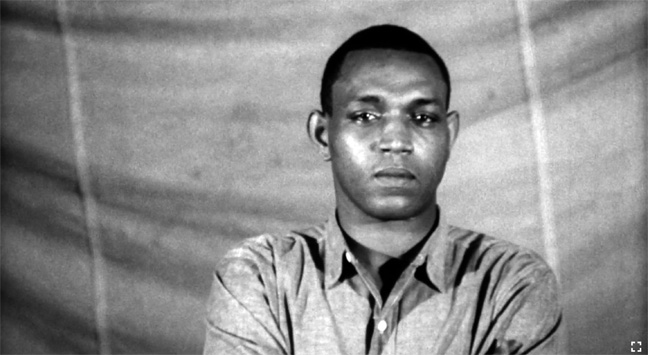

The lead role of Daniel, the black man at the center of the film, was credited to ‘Lewis Galen’: in reality, this was Raymond Aranha, an experienced and highly-rated probation officer for the Dade Juvenile Court. In his spare time, Ray was a keen thespian, and a regular member of local theatrical troupes such as the Coconut Grove Playhouse. Ray changed his name for the purpose of the film, realizing that the movie was bound to elicit strong feelings, and he wanted to protect his promising local government career. He later commented, “I wasn’t worried about the nude scenes. That’s life. It was the interracial part that would be an issue, and I knew I was in the Deep South.”

Ray Aranha (aka ‘Lewis Galen’)

Ray Aranha (aka ‘Lewis Galen’)

Then there was the role of Emily, the Shanty Tramp herself, the sexual temptress whose lustful feelings for Daniel cause the race riots. This role was played by ‘Lee Holland’: in reality, she was an attractive, quiet, and reserved Dade high school teacher called Eleanor Vaill. There was even a role for Vaill’s real-life husband, Otto Schlessinger, who played the part of her father.

Eleanor Vaill high school portrait

Eleanor Vaill high school portrait

Eleanor Vaill (aka ‘Lee Holland’) in ‘Shanty Tramp’

Eleanor Vaill (aka ‘Lee Holland’) in ‘Shanty Tramp’

For the role of the head of the motorcycle gang, Dolores suggested Lawrence Tobin, who had directed her daughter Marcy’s latest play at the Merry-Go-Round.

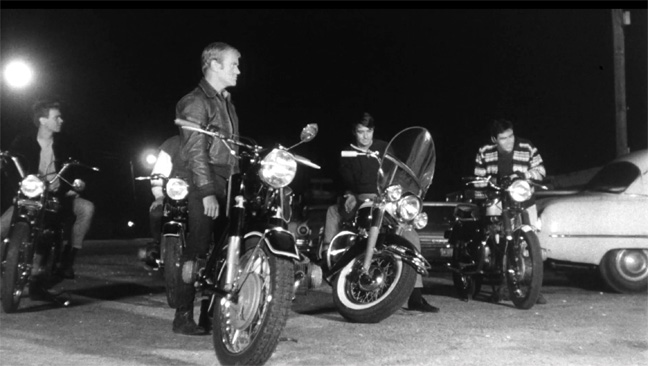

Then there were roles for extras and even they ended up being problematic: such as the vicious motorcycle gang. parts Somehow Dolores managed to convince four actual Broward County police officers to act in the film. She even got them to agree to use their police car – completely unauthorized, of course.

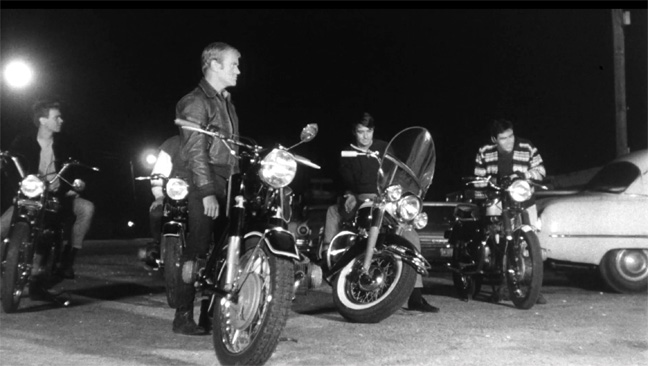

Lawrence Tobin (aka ‘Biker Savage’) and four Miami police officers (aka bikers)

Lawrence Tobin (aka ‘Biker Savage’) and four Miami police officers (aka bikers)

Ironically one of the only principal people who kept their real name was José himself, who finally came out of the shadows, anglicized his name, and became ‘Joseph Prieto.’

Most of the film was shot in the tiny Empire Studios in Dania, a neighborhood twenty miles north of Miami – even though the publicity would boast, “Filmed in the heart of Georgia’s emotional-infested swamps.” Some of the exteriors were shot on location at a local bar, and just to indicate the extent of the racial climate at the time, Lawrence Tobin, who played role of the amoral head of the motorcycle gang, later recalled that the lead actor, Ray Aranha, wasn’t even allowed in the bar to shoot the scene on account of his race.

Over the years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many of the people who appeared in front of camera in ‘Shanty Tramp’ or who worked behind it. I’ve been fascinated by the film, and keen to ask them for their memories. One common theme from these conversations is how clearly each of them remember the shoot – but more than that, how vividly they remember what happened next.

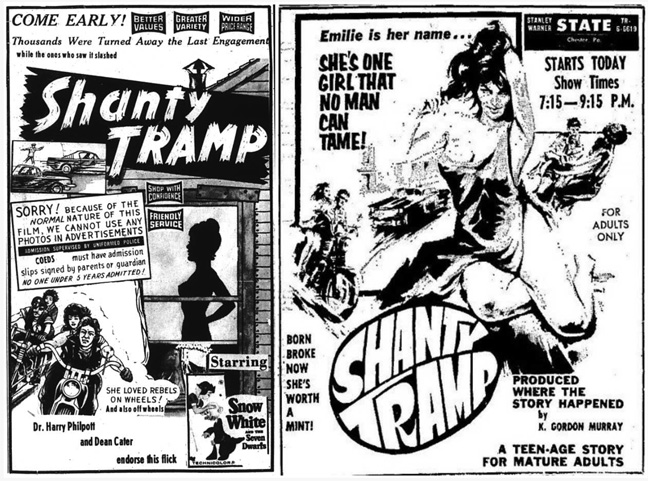

‘Shanty Tramp’ exploded onto the screens in June 1967. K. Gordon Murray had already told local newspapers that this was not an ordinary film event, and that he was entering it into the Cannes Film Festival. Radio and TV stations were bombarded with publicity for the film, and newspapers featured theater ads showing the poster for the film which featured artists impressions of scenes together with an explanation: “Sorry! Because of the abnormal nature of this film, we cannot use any photos in advertisements.” The ads also advised that uniformed police would be present to protect ticket buyers, and that viewers should “come early as thousands may be turned away.”

The blanket coverage in the newspapers was so extensive that the pages reserved for letters from readers was taken over by morally upright citizens writing in to complain… which of course only served to increase the film’s exposure. Sure enough, it played everywhere with playdates all over the country.

The film itself was certainly provocative. José and his Cuban crew filmed this Southern Gothic melodrama, poking every boundary and taboo and mining the material for every sleazy angle. The ‘n’ word was clearly used on several occasions in the movie, but according to several crew members, the producer Murray, writer Guberman, and director José changed their minds about leaving it in at the last minute. Using their dubbing expertise, the word was removed from the soundtrack before film prints were struck.

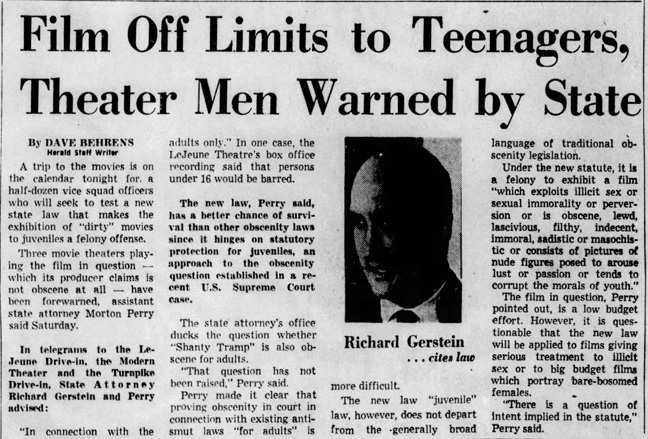

Attempts to tone the racial elements down though had no effect, and the outraged reaction continued. By September, the State Attorney warned any theater owners showing the movie were liable to be arrested under the state’s new obscenity law. The new statute centered around protecting juveniles from smut and violence, saying: “It is a felony to exhibit a film which exploits illicit sex or perversion or is obscene. By this we mean, lewd, filthy, lascivious, indecent, immoral, sadistic which intends to arouse lust or passion or to corrupt the morals of the youth.” As a promotional gimmick, Murray added a tear-off clip at the bottom of the newspaper ads, which read, “Teenagers! Have the Form Below Signed by Your Parent or Guardian! Sorry! You Will Not Be Admitted Without It!”

The Tropicaire Theater was one of the venues that was targeted by the state, and its manager was happy to oblige: “I’m pulling it,” he said to The Miami News. “This movie is too far out for me. Usually, these pictures don’t live up to the advance billing. But this one is for real.”

The State Attorney sent an investigator to view the picture, and his report confirmed their worst fears. It was swiftly reported in the newspapers. He wrote, “Various scenes depict prostitution, rape, incest, and even a sex orgy by a motorcycle gang. In the climax, a girl nude except for her panties is shown stabbing her father to death with repeated slashes of a butcher knife.” The investigator also noted that “the drive-in audiences were loaded with under-age viewers.”

The loud controversy was music to Murray’s ears. He declared the film was “a smashing success” at more than 1,000 theaters in the three months since its release.

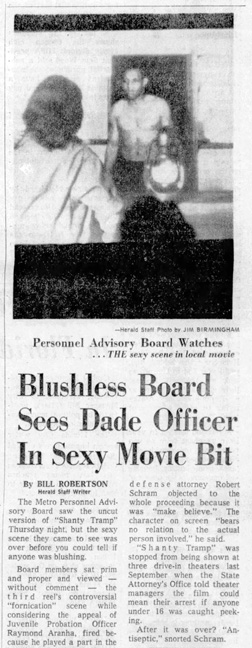

Up to now, the story had been one of a scandalous movie that may or may not be obscene that was raking in dollars at the box office. But the newspapers wanted more. They wanted a scapegoat. They discovered the background of some of the main participants: they found that the African American lead male was actually a probation officer, the nude hussy anti-heroine was a school teacher, and some of the biker gangs were cops. Bingo. The news coverage for the next months was taken up by the various arguments that followed.

Dolores took the breaking news badly. After all, she’d been the movie’s casting director, and had persuaded all these people to be in the movie. For the last years, she’d taken personal pride in helping people find film jobs, but now she felt personally responsible for the scandals that were about to engulf their lives.

The police were the first to be attacked. They started by arguing that it was a lie. Then they said that any footage of the four officers cast in the film had not made the final cut and so no transgression had occurred. Finally they conceded that the policemen in question had all been fired.

Meanwhile, Eleanor Vaill, the school teacher who’d used the name Lee Holland, was nowhere to be found. It was reported that, after being fired from her school job, she’d fled to Chicago – where she disappeared and was never heard of again. Actually none of that was true: Dolores had planted that story with the newspapers as a damage limitation measure to shield the ‘Shanty Tramp’ leading lady. In reality, Vaill had voluntarily left her teaching job and she was still living in Miami. In fact, she’d become a full-time actress, and continued to appear in local theater productions, including several with Dolores’ daughter, Marcy. Vaill and her husband did eventually move back to their home town of Chicago, where they became staples of the dinner theater circuit for years to come.

As for Ray Aranha, the African American who’d used the name ‘Lewis Galen’ for the lead role of Daniel, despite being commended for his work as excellent probation officer, he was nevertheless fired for being “guilty of conduct unbecoming of an employee of the county.” The case went to an industrial tribunal with ‘Shanty Tramp’ being shown to the panel of the Personnel Board, but Ray never got his job back.

I contacted Ray years later, and he laughed remembering the events of 1967. It turned out that getting fired was the best thing that happened to him, he said: “After that, I decided to focus on the theater – acting and writing. And that changed my life for the better.” Ray went on to significant success, winning the Drama Desk Award in 1974 for Outstanding New Playwright, and then acting on Broadway, in films, and on television many times in the years that followed.

While all the hoopla was playing out in the press and in the courts, and changing people’s lives forever, what was José’s reaction? After all, this was the man who had feared his name ever appearing in the news again. José had laid low, and somehow it worked. The cover stories and features and scandal had focused on nearly every aspect and every person in the film, except for him. Miraculously, he had remained anonymous.

When the dust settled, Murray sent him a bonus from the large profits he’d earned from the film: a check for $1,000. José, normally quiet and reserved, was in the mood to celebrate, and so he called up Rafael Remy and the rest of the Cuban expats who’d made the film, and they headed to the finest restaurant in Little Havana in Miami where José paid for everyone’s food and drinks.

The previous decade had been a strange whirlwind journey for him: José had gone from being a minor player in kick-starting the Cuban film business, to a major production director and acting gig in ‘Our Man in Havana’, before escaping Communist Cuba, and now directing a controversial race-baiting sex film. It was a lot for a quiet man to bear.

But those who knew him all agreed: he’d never been happier. He was back doing what he enjoyed best. So he went to see the management at the Everglades Hotel, his home and employer for the previous five years, and told them they needed to find a new bellboy.

He was a filmmaker again.

*

Tune in next time for another story in ‘Chasing Butterflies’.

The post Chasing Butterflies: Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida – Part 2, José Prieto’s story – Podcast 146 appeared first on The Rialto Report.

180 פרקים

Manage episode 447094644 series 2414495

Previously on Chasing Butterflies – Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida:

Manuel Conde had lived several lives even before he moved to Miami, Florida. He’d been born José Conde Samaniego in 1917 in Galicia, in northern Spain, though his family fled to Cuba after General Franco’s fascist coup d’état in the 1930s. And then, in 1959, Castro overthrew the government and enforced Communist rule over Cuba. Manuel, having already fled one dictatorship in Spain a few years earlier, took his family and fled to Miami, Florida, smuggling out a sexploitation film that he’d just made, called Girls on the Rocks.

In Miami, Manuel met Dolores Carlos. Dolores was a newly semi-famous actress and model on the local scene, having starred in (and been arrested for) a successful nudism film, Hideout in the Sun (1960) made by Doris Wishman, which she followed by appearing in a handful of other nudie cutie films.

Dolores introduced Manuel to the growing community of ex-pat Cuban filmmakers that had settled in south Florida after Castro’s coup, and together they shot a nudie short in 1961, Playgirl Models.

Dolores and Manuel arranged a meeting with Leroy Griffith, an energetic, entrepreneurial force of nature, who’d recently moved to Miami and made a name for himself by acquiring a string of theaters where he exhibited burlesque shows and then adult sex films. The three of them made a full-length feature was called Lullaby of Bareland (1964).

In 1966, Manuel and Dolores teamed up with Leroy Griffith to make a film with a decent budget – Mundo Depravados – starring Tempest Storm, one of the country’s best-known burlesque performers, and the movie was ostensibly directed by her husband Herb Jeffries, a suave and seductive film and television actor and popular jazz singer who had a large following in the African American market. ‘Mundo Depravados’ was released with eye-catching promo material – “A Sinerama of Sex and Fear!” – and is one of the most bizarrely entertaining film experiences you can have.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many of these people. Their overlapping personal histories reveal an untold chapter of adult film history and the hidden role that Cubans played in shaping it.

These are some of their stories. This is Chasing Butterflies, Part 2: José Prieto’s story.

You can listen to the Prologue: Dolores Carlos’ story here, and Part 1: Manuel Conde’s story here.

With thanks to John Minson, Tom Flynn, Ronald Ziegler, Leroy Griffith, Veronica Acosta, Marcy Bichette, Mikey Bichette, Lousie ‘Bunny’ Downe, Mitch Poulos, Sheldon Schermer, Ray Aranha, Manny Samaniego, Barry Bennett, Randy Grinter, Herb Jeffries, Tempest Storm, Chester Phebus, Michael Bowen, Norman Senfeld, Richard Falcone, Lynne O’Neill, Something Weird Video, and many anonymous families and friends who have offered recollections, large and small, over the years.

This podcast is 40 minutes long.

*

1. José Prieto – Timing

They say timing is everything. Sometimes it’s a well-oiled, precision-calibrated clock, but other times it just kicks you in the balls.

Take José Prieto, for example. It was the late 1950s, and here was a man who’d spent his entire life waiting for that big break that would give his life meaning, that would fulfill his dreams, but fate always seemed to be a case of wrong place, wrong time, and that elusive, life-changing moment of success remained forever out of reach somewhere off on the horizon. José was a small, wiry man, consumed by nervousness, and his world-weariness hung on him a cheap, oversized suit. His head seemed constantly lowered as if trying to figure out the answer to life’s latest conundrum. Some dismissed him as dour and uncommunicative, but José had close friends who knew the truth. Guys like Greg Sandor or Rafael Remy. They’d worked with him in the Cuban movie business over the years, stuck around to get to know the real José, and found him a quiet, thoughtful, smart, and diligent man. Funny and mischievous even, especially when he’d had a few El Presidentes in him.

José Prieto was Cuban-born and Cuban-raised. He’d lived in the country’s capital, Havana, all his life: it was a city of well over one million inhabitants, but it felt like a village to him. He mixed unobtrusively with everyone, from high-level government officials to pimps, petty criminals, and low-level gangsters. It wasn’t that he was particularly affable, but more because he wasn’t considered a threat to anyone. He knew his country wasn’t perfect: it was overseen by Fulgencio Batista, an un-elected right-wing military dictator who’d taken power by force in 1952. Batista’s regime was corrupt and becoming increasingly repressive, but José was smart enough to know the secret to living a comfortable life in Cuba was to fly below the radar and avoid the attentions of the men in power. If you kept your nose clean and your wits sharp, you could navigate this world comfortably.

And so, José had become a proficient jack of all trades in the Cuban TV and film business. The 1950s was a ‘Golden Age’ for Cuban cinema: it started when many American films were screened in theaters across the country, partly due to Batista’s close ties with the U.S. government and business interests – and then continued when several American films were shot in Cuba during this time, taking advantage of the island’s proximity and exotic appeal. Suddenly local studios were established in Havana which increased local TV production. Cuba became one of the first Latin American countries to introduce television in the 1950s, which quickly became popular, producing a variety of hit shows, including comedies, soap operas, and live music programs.

In a career that had been going over 20 years, José had produced, lit, shot, even acted in tens of these productions. Most of all though, he saw himself as a director, and occasionally he got the chance to be in charge. Some of his productions had been hits, others came and went virtually unnoticed, but he ploughed on, waiting for that one opportunity that would establish himself as a major player. But the Cuban film industry, for all of its strengths, was still small compared to Hollywood or Mexico, and the big breaks never came his way.

*

2. ‘Our Man in Havana’ (1959)

And then, José’s timing changed, and he was suddenly in the right place at the right time. It started when he read that Columbia Pictures were going to shoot a major motion picture right there in Havana. Not only that, but it involved three of his favorite people: it was to be directed by Sir Carol Reed, it would star Sir Alec Guinness, and it was based on a new book by Graham Greene named Our Man in Havana.

The story was a satire that mocked the intelligence services, especially the British MI6, and their willingness to believe reports from their local informants. Alfred Hitchcock had been the early favorite to make the film, but he backed out when he couldn’t afford the film rights to the novel.

José had read and admired the novels of Graham Greene, especially ‘The Power and the Glory’ and ‘The Heart of the Matter’, and his interest in the upcoming movie production only increased when it was announced that the film’s cast would include English acting royalty, Ralph Richardson and Noël Coward, as well as American stars like Burl Ives, Maureen O’Hara, and Ernie Kovacs, to help sell the film to an American audience.

José’s opportunity came in the last weeks of 1958, when Graham Greene and Carol Reed visited Cuba. They were there to do two things – view locations and hire the local crew. When they arrived, Reed was shocked and concerned by what he saw on the streets of Havana: signs that Batista’s regime had become more vicious were everywhere, and Reed was concerned about how filming could take place against the backdrop of such violence and intimidation, after all, Greene’s book was hardly reverential to the Cuban dictator. Columbia Pictures suggested a local production manager as a solution: a real life ‘man in Havana’ who could navigate the political and logistical roadblocks.

José saw his big chance and wrote to the studio asking to be considered. He was granted an interview, and made an impassioned case: he was more than just a fixer, he said. Havana was his backyard. He knew almost everyone, and if he didn’t know someone personally, well… he knew someone who did. He was experienced in putting together a movie production, he could arrange a complex shooting schedule, and he could do everything else that you couldn’t put a price on.

Where would they find film equipment? José assured them that whatever they needed would be delivered immediately.

Where would the best production accommodation be? José would get the choice rooms in the top hotel in Havana – the famous pink and white Capri Hotel, in reality, a casino cum whorehouse, owned by the Florida mobster Santo Trafficante, Jr., which was fronted by the entertainer, George Raft.

How would they find actors, or extras for the street scenes? José would produce any number of eager locals, excited to be in a big film production.

What about the nightclub scenes… where could those be filmed? No problem, said José. He had a cousin who worked at the Tropicana, Havana’s most notorious nightclub, another location owned by the mob. What’s more, he could arrange for strippers, bartenders, and local business men to be extras in the scene as well.

The production team was impressed. José had the experience, technical knowledge, and the network of contacts that they needed. He was hired on the spot, and in the records of the production, he was given the credit of ‘Assistant Director (Cuba location scenes)’. He even found jobs on the shoot for friends like Greg Sandor and Rafael Remy. Both had good credentials, having worked in local and international productions, Remy having already been an uncredited assistant director on John Sturges ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ (1958) starring Spencer Tracy, which had shot in Havana in the summer of 1956.

And then on January 2nd 1959, the revolution happened: Fidel Castro overthrew Batista’s regime and the situation in Cuba changed overnight: military thugs carrying sub-machine guns were everywhere and wagons laden with peasants in chicken-wire cages were drawn through the streets.

It was a strange time to be starting filming a satire about spying, but the news wasn’t all bad for the film production: Graham Greene had been friends with Castro since an earlier visit, and he wasn’t fazed by any new problems the coup would cause. After all, their film mocked the previous regime of Batista in an unflattering light and also condemned American and British meddling: surely Castro would welcome this prestigious film production – and appreciate the celebrities from England and the United States. The first signs were good: the new revolutionary government of Cuba gave the green light for ‘Our Man in Havana’ to be filmed in the Cuban capital, and so the production moved forwards.

But the same treatment was not applied to José. He was now treated with suspicion by the new leaders: Batista’s government had always let him do what he wanted but, bizarrely, he was now considered part of the former regime by Castro’s new government departments – and that made his new job rather more difficult.

His first task, before the film started, was to apply for work permits for everyone. This entailed taking the script to the new Ministry of Labor and justifying each cast and crew position to them. Castro’s men listened and then complained that the novel didn’t accurately portray the true brutality of the Batista regime.

Early Castro press conference, 1959

Early Castro press conference, 1959

Then José received an unexpected offer. The casting director told him they needed a local to play the part of Lopez, Alec Guinness’ assistant in the movie. When José found them a selection of actors, the production team was unsatisfied. The casting director replied that the ideal person for the acting role was José himself. It was a significant part, with plenty of lines and screen time.

José wasn’t keen. He was a background kind of guy, he said. Sure he’d acted before, but he was someone who preferred to stay in the shadows. His concerns were dismissed, and Alec Guinness was rolled out to try and convince him. Guinness took him aside and told him that both of their characters were anonymous personalities, mere cogs in the bigger story, men being manipulated by the machinery of government and men in power. Guinness said that it was important that neither of them acted: they just had to “be”. In that way, José’s personality was perfect for the role. In fact, his protestations were proof that he was the right choice. José was cornered: he’d idolized Guinness since the days of ‘The Third Man’ so how could he pass up the occasion to act with the great man? He reluctantly took the role – which he did in addition to keeping the job of local assistant director.

(l-r) Alec Guinness, José Prieto

(l-r) Alec Guinness, José Prieto

Filming started on location in Havana in March 1959 just two months after the overthrow of the Batista regime. On the second day of filming, José was approached by an official from the Minister of the Interior demanding a copy of the screenplay. José explained he’d already provided this to Ministry of Labor. That was irrelevant, he was told. Furthermore, they wanted a full translation – and, a censor would be sent to the set each day, in addition to a government observer, both of whom would shadow José and check that he was not doing anything that was “compromising the revolution.” It made José’s life more painful, especially considering that the Ministry of the Interior quickly insisted that 39 changes be made to make it appear that life during the Batista regime had been even more unfavorable.

At other times, José’s work on the movie was more comical but no less serious. Take beards for example: since Castro took over, a beard had come to represent a hero of the revolution. But one of the characters in the film – who played the role of Batista’s chief of police – had a beard. José was called in by the Castro officials and told that all beards in the cast and crew had to disappear.

Unwanted pressure didn’t just come from the new government, it came from locals too: when extras dressed up in the blue uniforms of the Batista police turned up for filming, they were attacked by angry spectators. Once again, José had to intervene to find a solution.

(l-r) José Prieto, Alec Guinness

(l-r) José Prieto, Alec Guinness

And then José got a message from Castro himself: the leader wanted to meet the people responsible for the production: Carol Reed, Graham Greene, Noel Coward and Alec Guinness. They were invited to Castro’s bungalow for the day. This would mean losing a whole day of shooting, so José went back and, in a diplomatic fashion, told Castro’s office that it would be difficult to accommodate. It was the wrong answer: José had greatly displeased the leader. He was dispatched back to the film set with a new instruction: the request had now become a demand, and the team were told to meet with Castro the following day.

So the next day, Reed, Greene, and Coward turned up for the appointment with an uncomfortable José lurking in the background. They waited for Castro in a palace room surrounded by bearded revolutionaries who informed them that Castro would be turning up shortly. Minutes turned into hours, and José’s unease turned into terrified concern. In the end, the film team left without a meeting. Castro had made his point. Days later, on 13 May 1959, Castro did meet the film crew when he visited the set while they shot scenes at Havana’s Cathedral Square. After he posed for pictures, Castro spoke to the press saying, “Any film company can make any picture they want in Cuba. There will be no censorship in my country. You can make the film exactly as you please. Those are my orders.”

(l-r) Maureen O’Hara, Fidel Castro, Alec Guinness on the set of ‘Our Man in Havana’

(l-r) Maureen O’Hara, Fidel Castro, Alec Guinness on the set of ‘Our Man in Havana’

Not strictly true, however. The on-set censor continued to make frequent demands to José that changes be made – in one of the nightclub scenes, for example, he felt that too much leg and breast was visible. Another time, he demanded that the whole day’s shooting footage be handed over to him for cuts to be made. But José had grown in confidence, and now he refused, standing up increasingly to the authorities, and invariably winning more battles along the way.

José did his job well in a way that few others in the world would’ve been able to do, and the film company was pleased with him. He’d done the hard, silent, behind-the-scenes tasks, delivering anything that was requested without fuss, in his usual intense, quiet, and serious manner. He earned the nickname ‘José Practical’ as a result of the calm, pragmatic way he worked.

(l-r) José Prieto, Jo Morrow, Alec Guinness

(l-r) José Prieto, Jo Morrow, Alec Guinness

But privately, José was far from feeling calm, and his fears were growing stronger by the day. He knew he’d be protected from Castro and his generals for the duration of the filming, but what would happen after the crew packed up and went home? He’d stood up to the government heavies on countless occasions during the film shoot, but how would they treat him in the future?

At the end of seven-week shoot, José started noticing things. Friends told him they’d been approached and quizzed about him. They’d also been asked questions about his local associates on the movie, like Greg Sandor and Rafael Remy. He noticed his mail was going missing, and he wasn’t paranoid by nature, but was he imagining it or was he being followed every day when he set out to go to work?

It was too much for the veteran film man. He called his contact at Columbia Pictures and asked to have his name removed from the credits of the final version of ‘Our Man in Havana.’ He got a mixed message. They told him they could drop the ‘Assistant Director’ credit, but that the acting credit was unavoidable. After all, his face was up there on the screen for all to see. José tried putting his foot down, but he was told that the best they could do was for him to use another name. José was relieved, but, somewhere along the way, the instruction was lost, and when the film came out, the name ‘José Prieto’ was prominently displayed in the credits – just after the big-name English and American actors.

José didn’t want to hang around. In the aftermath of the film, he wanted out before he got picked up and found himself in trouble. He packed his bags, and fled the country, heading over the sea to a new life in Miami.

*

3. Life in Miami

José didn’t move to Florida by himself. He was accompanied by his two main compadres in the Havana film business, Rafael Remy and Gregory Sandor. The grass looked greener on the other side of the water for all three, and so in 1961 they embarked on new lives in America. The U.S. was the center for capitalism and the center for filmmaking, right, so why not become part of the gravy train? They figured they could seek work quietly at first and earn a steady living in Florida. In fact, it was Sandor that facilitated their move as he was an American, hailing from Burbank, California.

Each of the three men wanted to continue working in the film business, but each had a different plan. The one thing they all had in common was that they wanted low profiles, to work under the radar, at least at first, with José especially fearing possible reprisals from the Cuban government.

Greg Sandor had it easiest: being an American who’d lived and worked in Cuba for years, he was the least worried. He was essentially a cameraman, who saw that his best opportunity would be in the world of commercials and industrial films.

For José and Rafael, it was more difficult. As new immigrants in the country, they headed to the Freedom Tower in Miami – the central location used by the government to process and document refugees from the Cuban Revolution that administered the Cuban Refugee Program.

Rafael Jesus Remy was always the more cavalier one. His plan for anonymity was to find film work, any film work he could, but use a variety of mildly different names to mask his participation. Sure enough, over the next years, he would be known as Jesus Remy, Gerry Remy, Ralph Remy, and many others – sometimes even his actual name Rafael Remy.

As for José, he was the fearful one. Film work was all he knew, but he’d had direct – and often confrontational – contact with Castro and his men, and so was reluctant to do anything that might draw attention to himself. He was the first of the three to find work – a lowly bellboy position in The Everglades Hotel, a popular mid-range option for business travelers in downtown Miami. It was a steep and strange decline in status for a man who was coming off being an actor and assistant director on one of the biggest motion pictures of the decade.

Everglades Hotel, Miami – late 1950s

Everglades Hotel, Miami – late 1950s

One night the three amigos found themselves outside a tiny shopfront in Little Havana in Miami with a sign outside advertising a fortune teller. They’d had a few drinks and laughed their way into the cramped room, where each sat on an upturned fruit basket and in turn had their future explained to them by a mysterious woman adorned in scarfs and jewelry. The mystic explained she used a combination of sacred instruments, including palm nuts, pieces of coconut, and Spanish tarot cards, to see into the future. She told them solemnly that Greg Sandor would find money and respect. José would find fame and notoriety. Then she paused, as if alarmed by the reading: Rafael Remy would find trouble and strife.

Inevitably perhaps, all three of the filmmakers came into contact with Dolores Xiques, now more commonly known by her film and modeling name, Dolores Carlos. She introduced them to the Cuban expat community, a group growing larger by the day but one that was still tight-knit. At the heart of it was Dolores, the caring mother hen looking after men from a country that she’d never visited but that she felt passionately about. She’d become the connective tissue binding the community together.

Dolores became particularly close with José. It was an unlikely friendship: she was an American single mother in her early 30s, living with her teenage daughter Marcy, and was the star of scores of nudie films and men’s magazines, who had the trust of film producers, theater owners, movie directors. and crew members. He was a dour, taciturn Cuban filmmaker in his late 40s, often paranoid and fearful, struggling with having left his country so hurriedly.

Dolores took José to see her friend K. Gordon Murray, the film producer whose company Trans-International Films bought children’s movies from Mexico and dubbed them for the domestic market. She was still trying to persuade Murray to finance nudie pictures, but apart from re-releasing a perfunctory effort called Eve or the Apple (1962), featuring nudie inserts of Dolores, she hadn’t had much luck in convincing him. He was making too much money with colorful, surreal fairytale films, like ‘Santa Claus’ (1959). But Dolores was persistent, convinced that Murray would eventually come good and move into film production, and she took many Cubans she met at the Freedom Tower to his offices at 530 Biscayne Blvd in Miami. Murray was impressed with José, especially when he recognized him from his appearance in ‘Our Man in Havana’. He found work for José on a variety of film projects, which José accepted if he could them fit in around his Everglades Hotel doorman duties.

Dolores also connected José with other filmmakers, many engaged in making South Florida nudie pictures. José became popular, willing to do a variety of jobs, invariably uncredited, often underpaid, but always skilled, professional, and useful. Just one job credited his involvement: an assistant director job for the Cuban man-of-many-hats, Frank Malagon. Malagon had set up a film studio to make films as a way of funding his anti-Castro activities, and his first feature was a nudist movie, Six She’s and a He (1963). Malagon’s partner, Richard Flink, was credited with directing the film but as neither Malagon nor Flink had much experience, it was largely directed by José himself. Many of the crew roles on the film, as with many other similar efforts at the time in Florida, were taken by expat Cubans – which made José feel at home.

In the early 1960s, in his first years in America, José worked on tens of films in an uncredited capacity. The Everglades Hotel provided him a one-room lodging in the basement of the building and he worked shifts there, so if was given enough notice, he could usually arrange to be free to work on a film set.

*

4. ‘Dios te salve, psiquiatra’ (1966)

In 1966, José received a call from his old friend, Greg Sandor. Sandor had done well since they’d arrived from Cuba. He’d found cinematography work on commercials in California, as well as camera work on a few exploitation films. His recent credits included a couple of Ted V. Mikels films, ‘Dr. Sex’ (1964) and ‘One Shocking Moment’ (1965), as well as two Roger Corman produced, Monte Hellman-directed films that starred Jack Nicholson ‘The Shooting’ (1966) and ‘Ride in the Whirlwind’ (1966).

Despite his growing success, Sandor had kept ties with his Cuban countrymen in Florida, and he had an idea for José. Sandor was helping another Cuban immigrant, Guillermo Álvarez Guedes, put together a Spanish language production, Dios te salve, psiquiatra (‘God Bless You, Psychiatrist’). Sandor said to José that the time had come for them all to come back and work together again just like in the old days in Cuba. Times were changing, he said, and José should be less fearful and more ambitious, and seek better quality film jobs. Sandor also enlisted Rafael Remy for the new film, as well as other members of the Cuban community in Miami.

José took some persuading: being a bellboy for the past years had been demoralizing at first, but it had given him an easy and quiet existence. Giving that up was a risk. José sought advice from Dolores and K. Gordon Murray and both encouraged him to strike out for himself, and return to more regular film work. Murray even promised him film projects that would be funded by his company. So José accepted the job of assistant director, on condition that his on-screen credit would only refer to him as ‘Pepe Prieto.’ He took a temporary leave of absence from the Everglades Hotel for a few months to be the assistant director on the film. The management at the Everglades liked José and were understanding, but also a little skeptical: they told him they’d keep his position open for a while – just in case this film malarkey didn’t work out.

(l-r) José Prieto, Guillermo Alvarez Guedes, Gina Romand

(l-r) José Prieto, Guillermo Alvarez Guedes, Gina Romand

‘Dios te salve, psiquiatra’ was a broad comedy of roaming love and Latin muchachos, and starred Gina Romand, a Cuban-born, big name in Mexican films of the time. It was a solid and bankable project, but most of all, it was a reunion of old friends: everyone returned to work for lower salaries simply because they wanted to re-connect with each other again. Talent that had been dormant for years suddenly returned to life. Dolores put together the promotional push that resulted in extensive media coverage and a big premiere. The film turned out to be a modest success in Spanish-speaking areas of the country.

José’s first job after ‘Dios te salve, psiquiatra’ was a quickie, Sting of Death (1966), about a deformed man working for a marine biologist who takes revenge on the people that mock him by experimenting with a deadly jellyfish. The film was another for the studio established by Frank Malagon, for whom he’d directed the nudist movie, Six She’s and a He (1963) a few years earlier, and José still just wanted his on-screen credit to just refer to him as ‘Pepe Prieto.’

And then Dolores called. Her long-term strategy with K. Gordon Murray was finally starting to pay off: after years of trying to persuade him, she’d convinced him to fund an exploitation film. Murray insisted that the craze for nudie movies had long passed: instead, he was looking at a more topical feature, albeit something that would still appeal to the sex-and-violence drive-in audiences, and he told Dolores that he’d found the right vehicle and wanted her help. Murray was looking to make a film that would hit the jackpot – and he wanted to know if José would be interested in directing?

*

5. ‘Shanty Tramp’ (1967)

Shanty Tramp (1967) is one of the most notorious, shocking and scandalous films of the 1960s. It tells the story of a sleazy evangelist who makes a play for a small town’s local tramp, but he’s shocked when he finds that she prefers a local black man over him. Furious, he stirs up the town against the couple causing fights, murders, lynch mobs, ruined reputations, and broken homes.

So who came up with the whole concept? The incendiary script, with plenty of nudity, sex scenes, and violence thrown in, was largely written by one of K. Gordon Murray’s staff members, Reuben Guberman. Guberman was a flamboyant New Yorker – or a “fat, Jewish maverick” by his own description. He’d left New York many years before as a teenager to seek his fortune in sunny Miami, Florida, and embarked on a ridiculously varied career that included being a hamburger cook, a drive-in restaurant manager, radio announcer and producer, editor of the weekly Dade County Times-Union newspaper, and political candidate. Perhaps his most surprising career move was discovering that he had a natural gift for lip-synchronization – an essential component part for dubbing foreign films and cartoons for Murray.

When Guberman met K. Gordon Murray it was a match made in heaven. Together they invented the looping process of dubbing: this consisted of splicing short segments of dialogue from a movie into a loop, and then playing them back to the voice actor allowing them to watch the film-loop over and over and record an English language track matching the on-screen actors’ mouths as much as possible. Working for Murray in his tiny office in nearby Coral Gables which he called Soundlab Inc., Guberman’s job was to translate the original language scripts into English dialog for the voice-talent, and in many cases, he also provided some of the voices himself as well.

But by the end of mid 1960s, the market for dubbed films was waning, and both Murray and Guberman were looking for a new market: they decided that ‘Shanty Tramp’ should be their next project. Murray and Guberman had already started to put the film together and hire a number of the actors when they offered the directing gig to José. José accepted even though he was still working at the hotel: he was hungry and ready to return to the party. Being the head-strong, stubborn guy he was, his first step was to fire most of the actors who’d been offered parts, and he assembled a crew almost completely composed of Cuban expats from his Little Havana hangouts. At the heart of the new film project was his old friend Rafael Remy who ended up doing both the cinematography and editing.

‘Shanty Tramp’ credits showing the Cuban crew

‘Shanty Tramp’ credits showing the Cuban crew

If the subject matter was akin to lighting a touchpaper of controversy, the casting of the movie proved to be a forest fire. José wanted proper actors for the lead roles, not the usual untrained and inexperienced sexploitation regulars, so he turned to Dolores and asked her to find suitable principals for the film. Dolores knew all the Cuban crew workers in Miami, but her knowledge of actors – especially serious thespians – was less thorough. She had an idea though: her teenage daughter, Marcy, had recently started acting semi-professionally with the Miami Merry-Go-Round Playhouse, and Dolores – ever supportive of Marcy’s endeavors – was a regular in the audience. She’d become friends with some of actors there, and successfully approached a number of them for the main roles in ‘Shanty Tramp.’

The lead role of Daniel, the black man at the center of the film, was credited to ‘Lewis Galen’: in reality, this was Raymond Aranha, an experienced and highly-rated probation officer for the Dade Juvenile Court. In his spare time, Ray was a keen thespian, and a regular member of local theatrical troupes such as the Coconut Grove Playhouse. Ray changed his name for the purpose of the film, realizing that the movie was bound to elicit strong feelings, and he wanted to protect his promising local government career. He later commented, “I wasn’t worried about the nude scenes. That’s life. It was the interracial part that would be an issue, and I knew I was in the Deep South.”

Ray Aranha (aka ‘Lewis Galen’)

Ray Aranha (aka ‘Lewis Galen’)

Then there was the role of Emily, the Shanty Tramp herself, the sexual temptress whose lustful feelings for Daniel cause the race riots. This role was played by ‘Lee Holland’: in reality, she was an attractive, quiet, and reserved Dade high school teacher called Eleanor Vaill. There was even a role for Vaill’s real-life husband, Otto Schlessinger, who played the part of her father.

Eleanor Vaill high school portrait

Eleanor Vaill high school portrait

Eleanor Vaill (aka ‘Lee Holland’) in ‘Shanty Tramp’

Eleanor Vaill (aka ‘Lee Holland’) in ‘Shanty Tramp’

For the role of the head of the motorcycle gang, Dolores suggested Lawrence Tobin, who had directed her daughter Marcy’s latest play at the Merry-Go-Round.

Then there were roles for extras and even they ended up being problematic: such as the vicious motorcycle gang. parts Somehow Dolores managed to convince four actual Broward County police officers to act in the film. She even got them to agree to use their police car – completely unauthorized, of course.

Lawrence Tobin (aka ‘Biker Savage’) and four Miami police officers (aka bikers)

Lawrence Tobin (aka ‘Biker Savage’) and four Miami police officers (aka bikers)

Ironically one of the only principal people who kept their real name was José himself, who finally came out of the shadows, anglicized his name, and became ‘Joseph Prieto.’

Most of the film was shot in the tiny Empire Studios in Dania, a neighborhood twenty miles north of Miami – even though the publicity would boast, “Filmed in the heart of Georgia’s emotional-infested swamps.” Some of the exteriors were shot on location at a local bar, and just to indicate the extent of the racial climate at the time, Lawrence Tobin, who played role of the amoral head of the motorcycle gang, later recalled that the lead actor, Ray Aranha, wasn’t even allowed in the bar to shoot the scene on account of his race.

Over the years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many of the people who appeared in front of camera in ‘Shanty Tramp’ or who worked behind it. I’ve been fascinated by the film, and keen to ask them for their memories. One common theme from these conversations is how clearly each of them remember the shoot – but more than that, how vividly they remember what happened next.